The Music Library at the Library of Birmingham looks at a “local” composer….

The recent WW1 centenary commemorations in Belgium brought the English composer Edward Elgar to mind, together with three largely unknown works he composed in support of that beleaguered country.

The invasion of Belgium, at the start of the war in 1914, generated a substantial wave of sympathy in the UK. A range of artistic individuals contributed to an homage called King Albert’s Book which was published by The Daily Telegraph at Christmas 1914. Elgar’s contribution was Carillon, a work for narrator and orchestra. This was the first of three works using the same scoring.

Carillon, op.75 (version for piano and optional narrator)

In it, Elgar sets a highly patriotic text by the Belgian author and poet Emile Cammaerts . The carillon of the title refers to the Belgian bell towers (as depicted on the cover), and I can imagine them, still standing, amongst the ruins and devastation of the German offensive. It’s noticeable that none of the impact of the invasion is shown in the cover design. The work was hugely popular in the UK, playing in London and on tour.

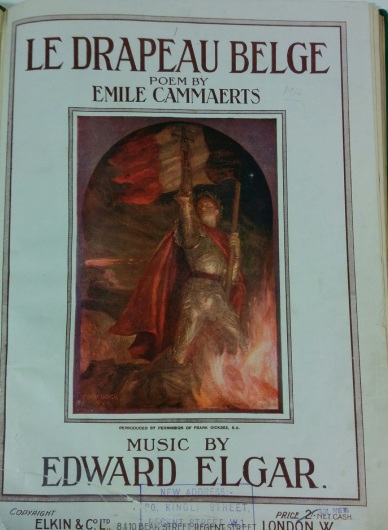

Le Drapeau Belge, op.79 (version for piano and optional narrator)

Again setting a text by Cammaerts, Elgar composed Le Drapeau Belge in 1917. The last of three works, it is also the slightest – a meditation on the colours of the Belgian flag. It is interesting that the cover art by Frank Dicksee is dated 1914. To me, the stirring, heroic image is so redolent of the opening months of the war. Of course, the intervening two and a half years had seen much fighting, horror, loss, and a distinct change in the public’s mindset. The reception given to Carillon wasn’t repeated when the new work was premiered in April 1917.

Une Voix dans le Désert, op.77 (version for piano, soprano, and optional narrator)

This stark, dramatic cover for the second of Elgar’s compositions is in such contrast to the other two. Here is no patriotic or sentimental fervour, but instead, a hint of the awful, bleak reality of Flanders’ fields. A desert indeed, but a man-made one. An artillery piece in the centre of the page reminds us how it was created. As do the crosses marking makeshift graves. The reddish pink is what? Reflected light from the sun, burning fires, or a reminder of blood?

The text by Cammaerts is the same. The opening stanza of Carillon is proud and patriotic in defeat:

Sing, Belgians, sing!

Although our wounds may bleed,

Although our voices break,

Louder than the storm, louder than the guns,

Sing of the pride of our defeats

‘Neath this bright Autumn sun,

And sing of the joy of honour

When cowardice might be so sweet.

Contrast this with the opening text from Une Voix (both in translation):

A hundred yards from the trenches,

Close to the battle-front,

There stands a little house,

Lonely and desolate.

Not a man, not a bird, not a dog, not a cat,

Only a flight of crows along the railway line,

The sound of our boots on the muddy road

And, along the Yser, the twinkling fires.

John Pickard in his notes for a Hyperion recording, calls it ‘a haunting, miniature masterpiece of great restraint and delicacy’. He also quotes a contemporary review of a staging:

It is night … [a] cloaked figure of a man, who soliloquises on the spectacle to Elgar’s music. … the voice of a peasant girl is heard … singing a song of hope and trust in anticipation of the day the war shall be ended. … he comments again on her splendid courage and unconquerable soul.

Other works that Elgar composed during the war included Starlight Express, which was performed at Christmas 1915, and The Spirit of England, first complete performance of which took place in Birmingham in 1917.

Re-blogged from the blog of the Music Library at the Library of Birmingham, with thanks to Anne Elliott.