One of the greatest joys of managing the early printed music at the Royal College of Music Library is getting to do what I like to call ‘treasure hunting.’ We are in a similar position to many other libraries around the country, I imagine, in that a portion of our special collections are so far not represented on our online catalogue. One of my main roles at the RCM is to work through our early printed collection and catalogue those items which for so long have been left untouched. Some real treasures – hence why I call it treasure hunting – have been unearthed during this process: autograph corrected proof copies of works by Holst, Coleridge-Taylor, and Elgar; an annotated score from Queen Victoria’s coronation; a presentation copy of Smyth’s Mass in D, complete with autographs of all the performers at its second performance; and even a very early English Bible, the Bishops’ Bible, published in 1585. A recent discovery, although of much narrower interest than the above examples, has taken me down quite the rabbit-hole recently.

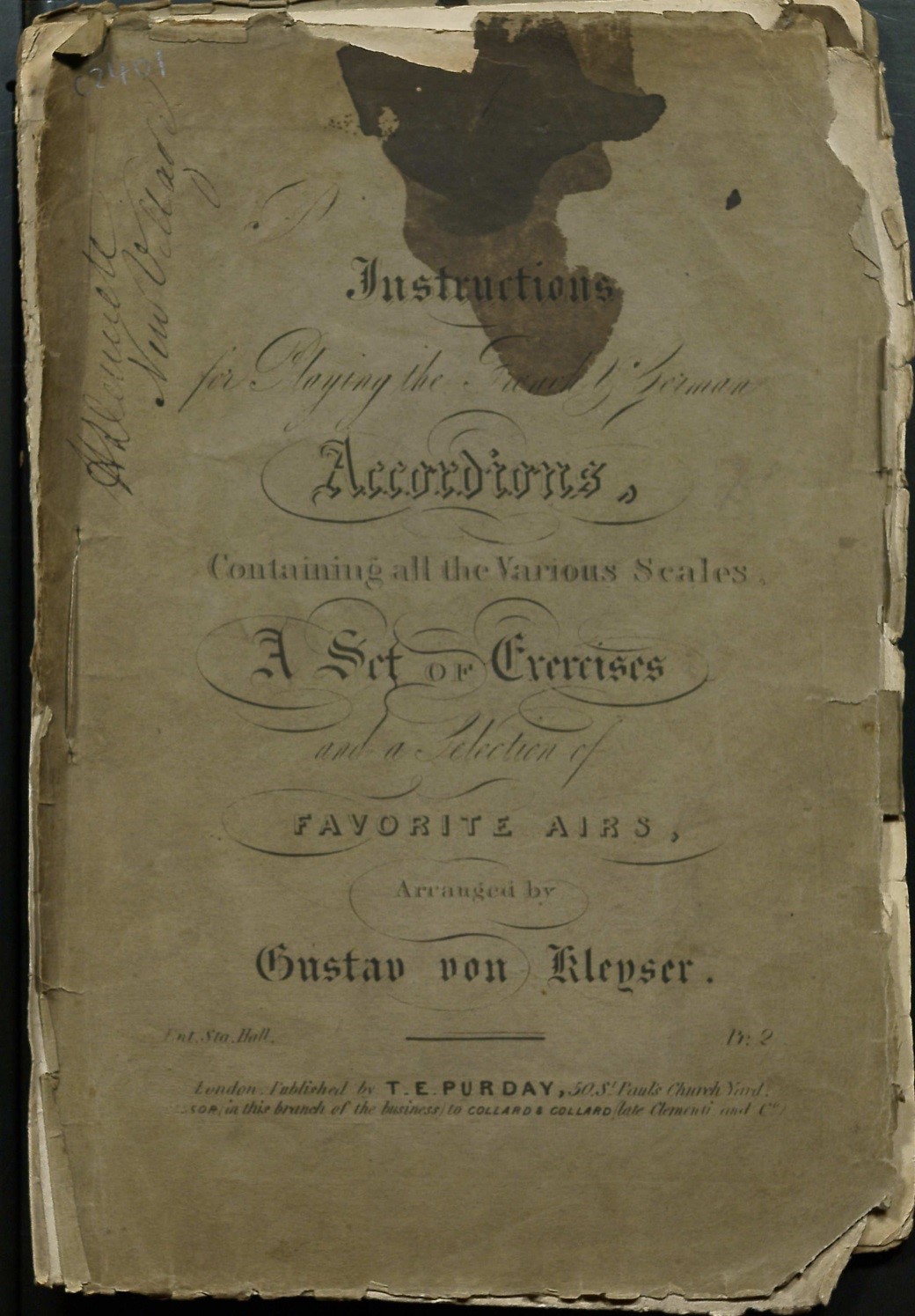

This rather battered, unassuming accordion tutor was published by T. E. Purday, and arranged by an elusive figure named Gustav von Kleyser. I know of no resource that can offer up any information on this gentleman, and the only other mention of him I have found is simply in reference to a later edition of the same work, held at Bibliothèque musicale de la Ville de Genève. The RCM copy is, to my knowledge, the only copy of the first edition held by any library.

Besides the obscurity of its author, on first glance there appears to be nothing too interesting about this item. In the style of the majority of method books of its day, it begins with a written section on the instrument in question, provides some fingering charts, and ends with some arrangements of the popular tunes of the day. (I use the word ‘arrangement’ in the loosest possible sense, given that these are mostly single melodic lines, firmly centred in the middle register, and could feasibly be played on any treble-clef instrument.) The author skips the customary ‘rudiments of music’ section, evidently holding accordion players in such high regard that he feels confident that they won’t need the basics of pitch and note lengths explained! There is a rather charming illustration of a party of splendidly-dressed men and women, either playing accordions or looking on admiringly.

Kleyser describes the accordion as a ‘new and most extraordinary instrument … with a sweetness of sound which far exceeds the most mellifluous notes that can be obtained from any wind instrument.’

High praise indeed! (As a wind player myself, I must confess that I would be hesitant to describe the accordion in this way.) Thrown off guard, perhaps, by this description, it did occur to me that maybe Kleyser did not have in mind the type of accordions we have today. So which instruments are we talking about, exactly?

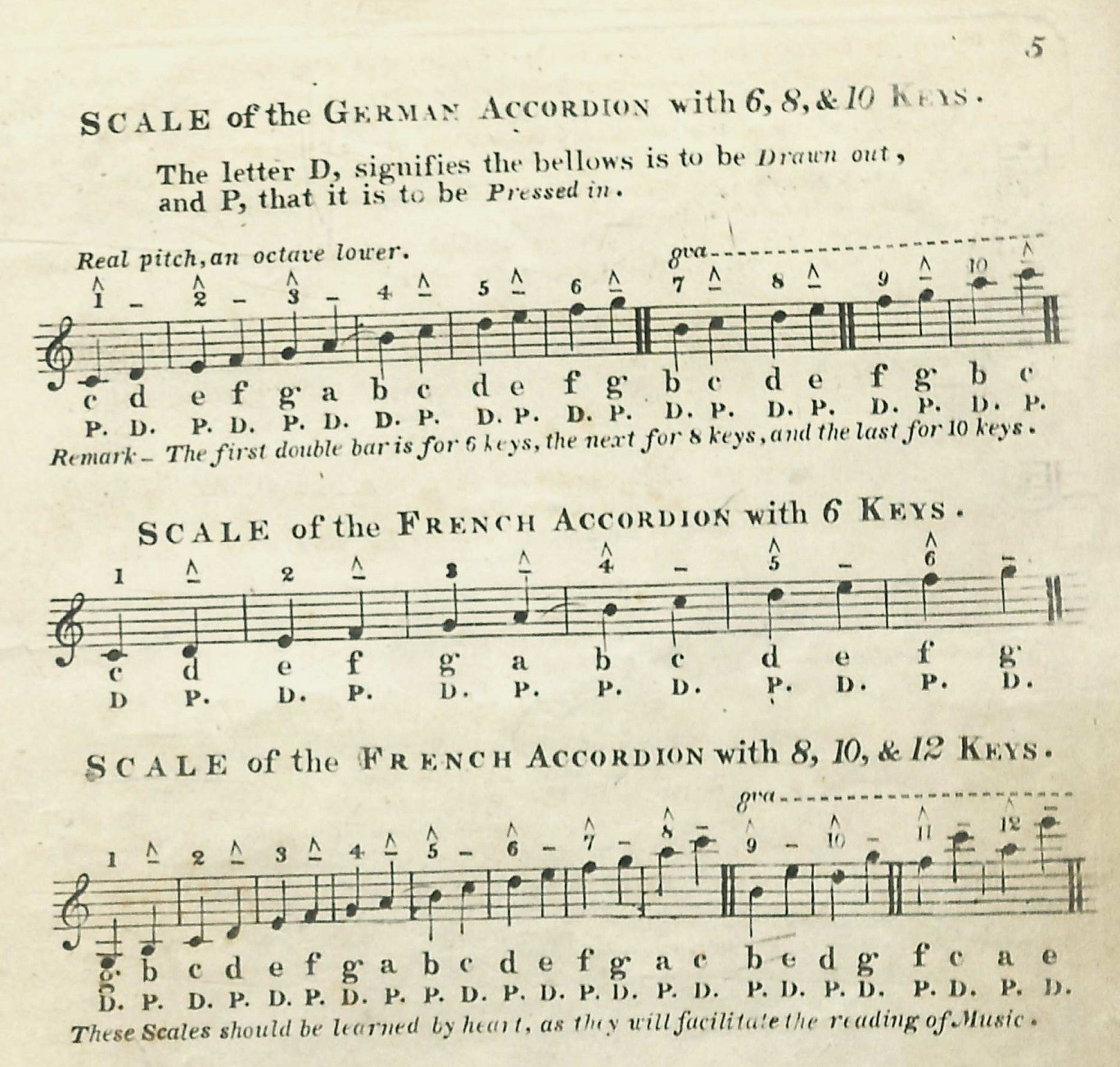

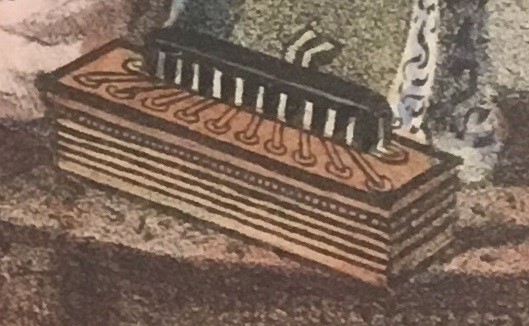

The accordion that most of us are familiar with has buttons on the left, a piano-style keyboard on the right, and is so large that it is mostly played sitting down. By contrast, the instruments pictured in Kleyser’s book appear to be much smaller, can be comfortably played whilst standing, and are described as being ‘so light, that a child may carry it under the arm.’ He also provides fingering charts for accordions having only as many as 6, 8, 10 or 12 keys, as opposed to the over 150 keys on a modern accordion. Having recently catalogued a large amount of concertina music, it did occur to me that perhaps the instruments pictured were concertinas: a sort of hexagonal, miniature accordion. Indeed, the concertina was sometimes referred to as an accordion. The concertina as an instrument has enjoyed enormous popularity over recent years, with at least 20 concertina ‘clubs’ meeting regularly in the UK alone (all of whom I have offended, no doubt, by describing their instrument as a miniature accordion). I soon found myself on concertina.com, and drawn to one article in particular: a discussion of the Earliest known English-language German concertina tutor, published in 1846 by Kleyser & Tritschler. The re-appearance of the name Kleyser seemed too large a coincidence to ignore. My (mistaken) belief that this was indeed a concertina method was cemented.

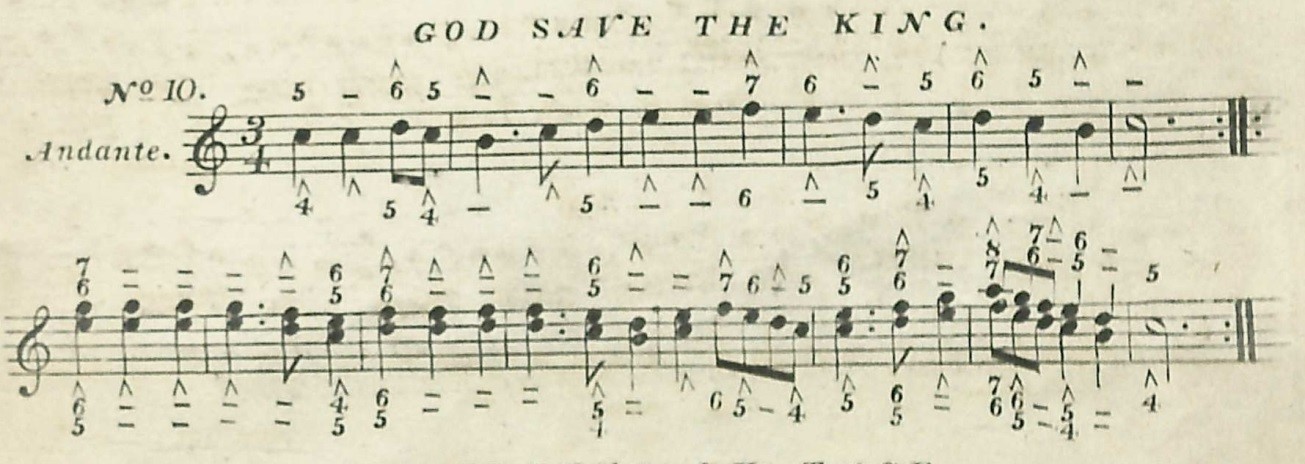

If Kleyser & Tritschler’s 1846 concertina method was the earliest English-language tutor known at the time of the article’s writing, where on the timeline does the present Instructions for playing the French & German accordions fall? Armed with Humphries & Smith, I learned that Thomas Edward Purday operated from the address given on the imprint between 1834 and 1862. A useful start, but still a rather large date range. In the absence of any biographical information about Gustav von Kleyser, I began to give up hope of narrowing this date range any further. That is, until I noticed Kleyser’s arrangement of the National Anthem. Entitled: God save the King. God save… the King. A quick Wikipedia search later, and it was confirmed: Queen Victoria succeeded King William IV in 1837, thus narrowing our date range to a mere three year span: 1834-1837. We can be very thankful that Kleyser chose not to entitle this arrangement simply, ‘The National Anthem’!

Elated in my (again, mistaken) belief that I had discovered an English-language concertina method predating the earliest currently known, I contacted the founder and webmaster of concertina.com, Robert Gaskins (who also happens to be the inventor of PowerPoint – that’s another story…), asking for his expert advice. He wrote back very promptly and thoroughly. I was, as you surely have noticed by now, incorrect about this being a concertina method. Mr. Gaskins observed that some of the accordions pictured in the illustration appear to be left-handed, whilst others are played right-handed (these being the ‘German’ and ‘French’ accordions respectively). A very detailed article by Stephen Chambers provides pictures and descriptions of ‘Viennese’ and ‘French’ accordions (pictures 8 and 9 of the linked article), which very closely resemble those pictured in Kleyser’s book (note in particular, the accordion sitting atop the piano, which has been drawn with great precision).

Chambers dates both of his pictured accordions to circa 1835, which would of course match my speculated date range of 1834-1837. At this stage, Chambers’ excellent article was able to satisfy my remaining questions. The accordion in this early form, having only been patented in 1829, was seen in London as early as 1830, and a tutor was published for it the same year. This Kleyser tutor, therefore, may not be the earliest, but certainly dates to within a decade of the accordion’s invention, and does appear to have been previously unknown in this first edition.

Is there a connection between accordion-lover Gustav von Kleyser, and the concertina publishers and manufacturers Kleyser & Tritschler? Unfortunately, this remains to be answered, although I would invite your speculations. Since Kleyser writes so forcefully about the accordion, I should be a little disappointed to learn that he took up with the new-fangled concertina so soon afterwards. I leave you with a passionate excerpt from his writing, which commends the accordion strongly enough to soften the heart of even this most hardened wind player…

These singular advantages at once account for its being so very fashionable; and, with the present reduction in price, cannot fail of establishing it as a permanent musical instrument, than which, none can be better devised, to develop and direct the musical feelings of the beginner, to communicate to him the meaning of the various expressions belonging to music, and to display all the delicate discrimination, refinement, and impassioned energy, of the most vigorous and accomplished performer.

Instructions for playing the French & German accordions is currently on display at the RCM Library.

Jonathan Frank, Assistant Librarian, Royal College of Music