A few months ago an email appeared on the IAML list asking for articles for the latest edition of CILIP’s Catalogue and Index journal. This was going to be a particularly unusual issue in that it was going to look at items that were rather outside the usual cataloguing norms. As any music cataloguer will know, mention that you’re a music cataloguer to a fellow librarian, and the reaction is usually a mixture of awe and a “S/He must be completely mad;” I just had to write something.

Inspired by the email asking for articles on “weird” items, the essay was first published in Catalogue & Index Journal, Issue 189, December 2017; which also featured some fascinating articles from cataloguers at the British Library on their work with sound recordings, the difficulties of finding authors, titles and publishers when cataloguing artists’ books (thanks to Maria White at London Metropolitan University for revealing an unexpectedly thorny problem), and (my particular favourite) how do you catalogue a toy volcano? – a must know, courtesy of the Bodleian. Thank you to the editors of the journal for giving me permission to republish here…

After a long line of music related jobs (with the odd diversion into the world of Samuel Pepys), I accidentally fell into work at Cambridge University Library Music Department in 2002. Probably because of my musical background, cataloguing scores has never felt particularly unusual to me, though I know that many cataloguers think that it is an alien land. In general, music cataloguing has much in common with standard book cataloguing, but there are distinctions, so having some level of musical knowledge is vital, even in the simplest areas. For example, a few months ago we received a score and a set of parts for a string quartet. Score (as you would expect for a standard string quartet) was for two violins, a viola and a cello. Unfortunately, there had been a bit of a mix-up with the parts, and we ended up with four cello parts – not what we were expecting at all, and a disaster for anyone wishing to play the work. It would be rather like ordering a complete tea service and discovering that only saucers were included.

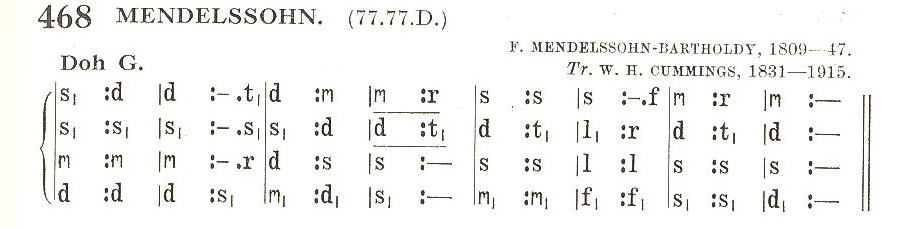

One area that is generally more complex than most in regular cataloguing is the creation of uniform titles. These can be tricky because of the frequent use in music of generic titles – symphonies, sonatas, and so on. Once you have recognised the generic component, you then need to include the medium (i.e. what instruments you need to perform the work). Numbers associated with the piece – op. 10, or op. 10, no. 3, for example – are added to the title, along with the key, which if not indicated on the title page, will need to be identified by the cataloguer, so a level of musical fluency and confidence is essential. To add to the complexity there are probably not that many cataloguing jobs where you regularly have to catalogue items in such a variety of languages. In my time as a cataloguer, I have catalogued music with title pages, or lyrics, in just about every European language, and several different scripts. The most unusual language must have been that of a hymnal published in Ponapean – Pohnpei is a tiny Pacific island (it’s a little smaller than the Isle of Wight) in Micronesia. Although most of my work revolves around standard notation, other unusual forms of notation do turn up, including graphic notation and sol-fa, which was very popular especially in choral music and hymnals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

I love working with music. It is endlessly fascinating, and you never quite know what you might find. One of my favourite cataloguing adventures involved the discovery of a lost musical work that even the composer had forgotten. You may think that this would be more likely to happen with an older work, but there are surprises…

For some time, I was the Archivist of the William Alwyn Archive here at Cambridge University Library. William Alwyn (1905-1985) was a British composer. If you have a feeling that you have seen his name before, it will probably be because he is best known even today as a composer of film music. His name can be seen on many a film credit from the late 1930’s to the early 1960’s. He worked with the director, Carol Reed (uncle of Oliver Reed, who was a memorable Bill Sykes in Carol’s Oscar winning musical Oliver!), played billiards at his club with ’30’s hearthrob and Oscar winner, Robert Donat, and was close friends with much-loved percussionist, James Blades, who was responsible for the sound of the Rank gong at the start of many of their films. Alwyn even worked for Disney, though he resolutely refused to move to Hollywood, preferring the atmospheric salt-marshes of Suffolk, where he spent much of the latter part of his life with his fellow composer and second wife, Doreen Carwithen.

The music that we have in the Alwyn Archive, as is common with other composer and author archives, includes works at different stages in their evolution. There are early sketches ranging from very rough drafts and jottings of potential themes, to almost complete scores; there are finished scores by the composer ready to send to the copyist; and finally, scores and parts in a copyist’s beautiful hand. The music copying trade has largely been forgotten, but long before the days of easy online publishing, a huge number of copyists were found across the UK. They were vitally important in translating the composer’s manuscript (which was not always that legible) meticulously by hand into an easily readable score that could be used by the orchestra conductor, and any technicians involved in recording the music. They also had to copy out individual parts for performers. For a large-scale work perhaps involving an orchestra, and soloists, this might mean copying upwards of 100 parts. The majority of copyists were female as it was an easy job to do from home. This was vitally important in a period when women were often discouraged socially from going outside the home to work post-marriage and children.

Among the manuscripts, that I came across in the Alwyn Archive was a group of sketches and a score for a film with the cryptic title “R.K.O. film”. In amongst this group of sketches was a single song, labelled as coming from the film, Escape to Danger. Premiered in 1943, it was a low budget film directed by Lance Comfort, and starring popular British actor Eric Portman. The film was released by R.K.O, an American production company, who also acted as a distributor for a number of companies worldwide. Most early Disney feature animations, for example, were distributed by R.K.O.

Alwyn remembered writing the score for Escape to Danger, so both the composer and his widow had assumed that the sketches and score all related to the same film. However, as I started to leaf through the sketches, I realised that there was something wrong with this. Film music is easily recognisable, as it includes cues matching music to the on-screen action. A few of the cues that I first came across included “Nazi ace” and “Kohler and Mrs. Krohn at telephone”. Although Escape to Danger was set during the Second World War, the characters mentioned did not appear to feature in the film, as a quick look at the British Film Institute’s helpful online database soon revealed. So, what film score was I actually looking at?

Several references to “Eric” suggested that this film too starred Eric Portman, so I started to look up any characters that he had played that matched the names I had found. Sure enough, there was another R.K.O. film made at the same British studio that year – Squadron Leader X. It transpired that Squadron Leader X and Escape to Danger had been made back-to-back, with Escape to Danger going into production just as Squadron Leader X went into post-production. The two films not only shared the same director and leading man, the entire cast and crew had been transplanted straight from one film to another. It is hardly surprising that William had become so confused that he had completely forgotten that he had written TWO scores and not just one. It was very satisfying to be able to resurrect a lost film score, especially as both the films concerned vanished many years ago.

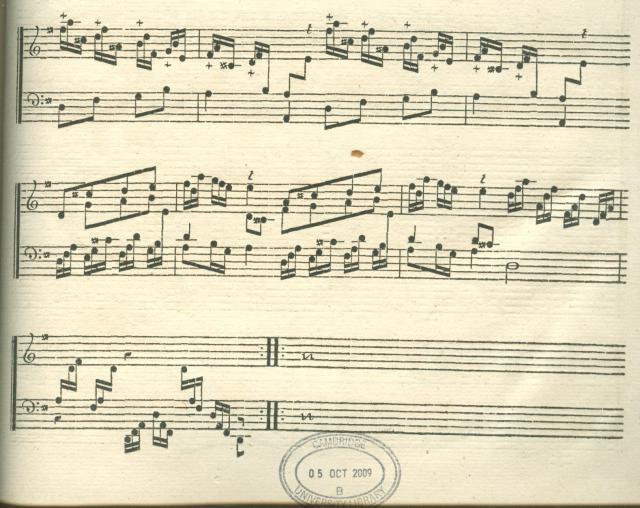

Another unusual item that I was lucky enough to catalogue, this time from a much earlier period, was a set of harpsichord sonatas by Giuseppe Sarti (1729-1802). The sonatas lacked a title page and the last page of music, but were published using an unusual kind of music moveable type designed by Henric Fougt (aka Fought), a Sami, who had started his printing business in Sweden.

Thanks to the papers of H.E. Poole housed here at Cambridge University Library, I was able to piece together the history behind Fougt’s business venture. H. Edmund Poole was a former librarian at Westminster Public Library, and a mine of information on the history of printing, especially regarding music. Much of the information about the life and work of Fougt referenced here was placed in a folder by Poole, while he was researching New music types: Invention in the eighteenth century I, published in Journal of the Printing historical society 1, 1965.

Fougt’s first job was as a mines inspector in Sweden; his work as a mineralogist brought him into close contact with the botanist, Linnaeus – he even contributed to one of his papers. An interest in printing and a judicious marriage to Elsa Momma, daughter of the Royal Printer, allowed Fougt to turn his hobby into a career. Having studied the new system of movable type recently developed by J.G.I. Breitkopf (still a major player in the world of music publishing), Fougt realised that there was a potential market for cut-price music, and produced a cheaper version of Breitkopf’s musical type, which he then presented to the Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Academy were initially enthusiastic about the business proposal, but other authorities needed to be convinced that the business was likely to make money, as, it was widely believed at the time (it now appears erroneously), that the Breitkopf scheme was running at a loss, so Fougt’s request for an exclusive privilege to print music in Sweden was turned down.

Fougt continued to fight for a place in the Swedish musical establishment, undercutting his own father-in-law in a bid to further his print business, but the lack of financial and state backing, coupled with an increasingly unpleasant atmosphere with the in-laws led to a relocation to London. This involved the costly process of shipping all his type over to England; but it was there, in December 1767, that he finally received a patent for “Certain new and curious types by me invented, for the printing of music notes as neatly … as hath been usually done by engraving…”. Around 1768 he moved from his first home in England to St. Martin’s Lane, and the delightfully named “at the sign of the Lyre and Owl”. Here he initially sold editions of sonatas by Sarti, Uttini, and Sabatini, along with music stationery. Some researchers have speculated that Fougt may have penned some of the musical works he published, the composers themselves seem to be generally little known, perhaps some of them were Fougt under another name?

By April 1769, the business had expanded and sold musical instruments, songs by popular composer Charles Dibdin, and ballads for just a penny a page. Prior to Fougt, a page of music was more likely to sell at around 6 pence a page, so there was a sizeable difference in the way he marketed popular music. Items printed by “H. Fougt, Musical Typographer” soon sold in shops across London and Oxford and business seemed to be doing well; but Fougt’s assault on the British music market conspired to make him less than popular with his fellow professionals, and ultimately led to his demise. It is puzzling as to what exactly went wrong, but in April 1769, an advertisement appeared in The Public Advertiser announcing a new work by Charles Dibdin, The Padlock. Music was available direct from the composer, or from his printer, Fougt. However, by July, the relationship had soured, and the following notice appeared in the same journal:

“Some of the songs in the comic opera of The Padlock having been pirated in a collection of vocal music; a bill was last week filed against the publisher…And the proprietor has given orders to prosecute one, Fought [sic], a foreign printer, in what he calls musical types, for an offence of the like nature; which he is determined, for the sake of musical property in general, to carry as far as the law will admit. And in the meantime it is hoped that no music shop will encourage by their countenance, such unjust and infamous practices.”

It is not clear exactly what happened next, I have found no trace of a prosecution, but following the threat from Dibdin’s publisher there are few advertisements for Fougt’s publications. The wording of the advertisement suggests that the “prosecution” was inspired by xenophobia as much as by a genuine fear of piracy – much is made of Fougt’s status as a foreigner, and his undercutting of the music printing market would not have made him any friends. Twenty years on, Dibdin was still fighting the pirates, so although it is likely that Fougt was indeed one of many abusing the law at the time, he was probably unlucky in that he happened to be the one chosen to be an example to others. By 1770, Robert Falkener had taken over Fougt’s presses and type patents, and was selling music successfully from an address in Salisbury Court, near to where Fougt had first traded in England. Fougt meanwhile hopped on a boat bound for Sweden, and was never to set foot abroad again.

He eventually became Royal Printer, following his father-in-law’s example, and remained in this post until his death in 1782, with his widow Elsa continuing to run the business for the next 30 years. A pioneer, who tried to make sheet music accessible to a wider audience, it is more than likely that at least at one point in his life Fougt was guilty of musical piracy so there is a certain irony that some of his music has found its final resting place in one of the UK’s Legal Deposit Libraries.

For more on Fougt’s career, and a possible side-line in composition see Nils G. Wollin, Det första svenska stilgjuteriet: Studier I Frihetstidens boktryckarkonst, (Uppsala: Almquist ochs Wicksell, 1943), and Åke Vretblad, “Henric Fougts engelska musiktryck” (The English printed music of Henric Fougt), Biblis: Årsbok utgiven av Förening för Bokhantverk, 1958.

Margaret Jones (Music Collections Supervisor, Cambridge University Library). With thanks to Deborah Lee, CILIP Catalogue and Index Journal, and Cambridge University Library.