Karen McAulay gets in touch with her Inner Geek…

It is strange to think that only a decade ago, hardly anyone would have heard of big data. For something so large, it’s relatively easy to get your head around the concept. Big data is where you assemble such an enormous quantity of digital data that you are able to analyse it and make it tell a story. A fascinating story, in fact. (Or am I just such a geek that it satisfies some geeky need deep within myself? No, that can’t be right – because there are plenty of other people equally enthralled with it!)

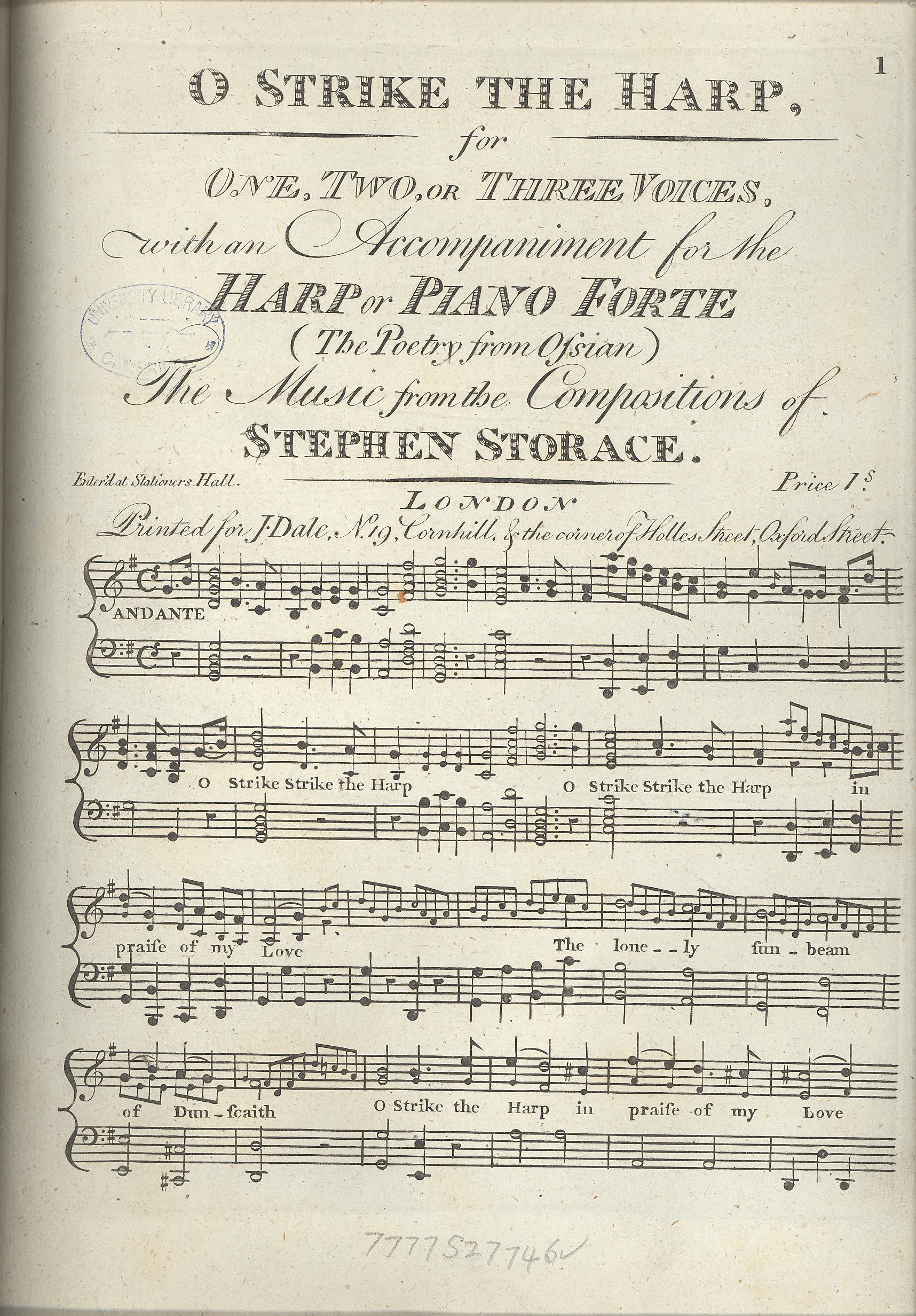

With kind permission of the British Library.

In order to work with “big data”, you need a high volume of data, high velocity and high variety; perhaps unsurprisingly, a great amount of work has already been done in the sciences. However, the Arts and Humanities Research Council funded three projects involving music, because they wanted to get the compilation and analytical research processes used more within the arts. At this year’s recent IAML (UK & Ireland) Annual Study Weekend, Sandra Tuppen spoke about the AHRC-funded project that she has been working on: ‘A Big Data History of Music’ (for their blog see here). Royal Holloway (part of the University of London) and the British Library worked together on this project under the direction of Principal Investigator Stephen Rose of Royal Holloway, with Sandra herself as Collaborator. The project ran from January 2014 to March 2015. Other AHRC-funded big data projects elsewhere involved audio analysis and optical character recognition of music.

Sandra explained that their project worked with large datasets gleaned from different kinds of bibliographic records: RISM A/1, for pre-1800 music (making use of electronic data that is not yet fully online for regular access); RISM B/1 for printed anthologies; the RISM online catalogue of manuscripts from 1600-c.1850; and the British Library catalogue. Dates of publications and manuscripts are crucial for a historical approach, of course, and Sandra demonstrated graphically what happened to the statistics if one failed to take into account things such as estimated decades where no publication or other accurate date could be established by a cataloguer.

The big data history of music most dramatically demonstrates trends in sixteenth and seventeenth century music publishing, and little-known composers’ names rise to the surface where there turned out to be far more publications than one might have imagined. For example, 9,000 composers’ works got into print in the 17th and 18th centuries, and much more has been identified in manuscripts from the 17th to 19th centuries. Political events and cultural affairs are also reflected in the big data results, as in the case study of Scotland-themed publications where there was a big rise in so-called “Scottish”, or “Scotch” music around the Ossian era, peaking around the 1780s, dipping around 1820 and then rising again as Queen Victoria’s love of Balmoral and things Scottish led to another surge of enthusiasm for Scottish song.

A Stephen Storace setting of O strike the harp

Sandra observed that the low point in these “Scottish” publications in the 1820s was rather surprising. However, I can think of various things that were also going on in the cultural scene around then. The Ossian craze was lessening, once the author James Macpherson’s fabrications were found out and acknowledged. Music actually published in Scotland was being simultaneously published in England in any case, so there may have been less demand for ersatz material. The ballad opera era with its plethora of “Scotch” and “Jocky and Jenny” songs had come to an end. And Sir Walter Scott had put tartan on the map with his stage-managed visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822. Scotland, for long enough a reluctant part of the United Kingdom, was – for now at least – more accepting of its British monarch and Britishness, whilst still remaining proud of its own cultural identity. But perhaps this easier relationship of Scotland with England might have been another reason for less production of “Scottish” material compared to the late 18th century. If you can get the real thing, why settle for anything less? It’s not as though none of it was being published, in any case – just a lot less than at the Ossianic apogee.

Other case studies looked at Palestrina’s and Purcell’s music, in terms of which genres and places produced the most Palestrina materials; and where Purcell’s manuscript anthems survived most plentifully, indicating the places where the repertoire was most popular.

In conclusion, Sandra reminded delegates that the RISM data could actually be inspected via the Open Data Service, as could the British Library open data. Those unafraid of RDF/XML and with a healthy curiosity in facts, figures and statistics, were urged to take a look, and all were reminded that Sandra and the rest of the project team would welcome feedback.

Reblogged this on Karen McAulay Teaching Artist and commented:

In which I recall another of the highlights of the IAML UK & Ireland Annual Study Weekend 2015…

[…] find the answer to what we now consider to be basic questions. Online data in general and “big data” in particular open new ways of doing research, enabling us to find a relatively quick answer […]

[…] & Ireland) 2015. See ‘ASW 2015: The Bigger, the Better – A Big Data History of Music’ https://iamlukirl.wordpress.com/2015/04/17/asw-2015-the-bigger-the-better-a-big-data-history-of-musi… (17 April […]